Part II.

The next example of Gordon’s work is Through a Looking Glass (1999) (Fig v). This piece is a visual representation of a psychological process. The work is taken from Martin Scorsese’s (1942- ) Taxi Driver (1976) and shows the sequence where a psychotic Travis Bickle played by Robert De Niro (1943- ) is talking to himself in a mirror. The scene is played on two screens which face one another with a thirty foot gap in-between. Gordon states that “Something happens between the surface of the glass and the silver reflected surface”[1] and in doing so he desired to make this quarter inch gap in the mirror into a thirty foot gap that the viewers could place themselves in. To use a relevant account from the artist:

Wouldn’t it be really great to expand that thickness in order to step in – I don’t want to be on that side of the mirror or the other side, but half way…to extend this space and therefore to have one foot in the fantasy and one in the reality.[2]

This indicates how narrative is often disposed of when recalling a film, and how these recollections then merge with personal memories. This is something that also links with Through a Looking Glass and has been acknowledged by the artist’s own explanation of the piece. If you transpose the word “fantasy” for “film” in this last recollection from Gordon, it is quite conceivable that this piece acts as a visual comparison of Burgin’s theories. To ‘have one foot in the fantasy and one in the reality’ exemplifies what Burgin is at lengths to portray in his book: that the visual experiences taken from film, will often ‘merge’ with those taken from reality. Our recollections from fantasies become part of our associated and connected realties. Consequently it seems entirely conceivable to see a work like 24 Hour Psycho as another view of a psychological occurrence. As the images on the two screens, played at different rates, start to become totally out of sync with each other, this monologue turns into a dialogue. Being stuck in-between, the audience attempts to translate this confused state. This confusion, once again is mirrored by the viewer’s recollection of the relentless images. Fiction becomes reality and visa versa; much in the way one remembers one’s own life.

The idea of the indistinguishable nature of fact and fiction, through certain remembrances is also evident in Gordon’s quasi-autobiographical book What Have I Done, produced for his retrospective at the Hayward Gallery in 2002. This short book - a strange account of Gordon’s early life - has no obvious narrative flow and is far more descriptive than linear in its narrative development. It provides a few crucial aspects of Gordon’s account of his upbringing and these make an important contribution to this paper: firstly, in this book his memories have no beginning, middle, end, and therefore any defining narrative features are abandoned. This echoes many of Burgin’s judgments on memory and its disjointed nature. Secondly, his recollections seem to be a mixture of fact and fiction. They produce a sensation of fantasy constantly. And crucially, the film and literary works are placed side by side, and become synonymous with ‘actual’ events; again, as has been described in The Remembered Film. And thirdly, the character of ‘Jimbo Park’, Gordon’s childhood friend and ‘Interlocutor’ (perhaps his imaginary friend?) features throughout. He starts to act as a kind of alter ego - a theme also significant to his work - who films Gordon and gets him into trouble. In my view this is a depiction of Gordon the artist, who deconstructs, analyses and documents the events which unfold.

The following section from Gordon’s book is used to demonstrate the notion of the film being ever present and a part of associated memories - and describes him being watched by an ever present alter ego:

There was always two of us: I was born with a person watching at my side. There was always two. Myself and my interlocutor; the child on the rug; tasting sherbet, watching James Cagney films on TV, James Cagney’s face and his jerking shadow beside the electric chair, or James Cagney on top of the burning building, that James Cagney, the one that lives in my own nerves and in my blood throwing down his gun and shouting to his mother…our first video machine, at midnight I came down to see it and noticed him there...There was always two: I called him Jimbo Park.[3]

It is clear from What Have I Done that Gordon places great significance on film, popular culture, literature, religion and his Scottish working class roots as part of his upbringing. In the book, these aspects of his youth blend with the lived events that surround them; highlighting their fictional characteristics and producing a sensation of childlike fantasy in the reader.

He continues:

We told the church minister Marilyn Monroe was more alive than the girl next door and the girl next door was more alive because of Marilyn being on the television one night in Bus Stop while she, the girl, was dyeing her hair, waiting for the phone to ring. Jimbo was good for a laugh. ‘We faced death like John Wayne,’ he said. ‘Like Montgomery Cliff. Like Peter Pan. Like Harold Lloyd.’ The minister took me by the ear. [4]

Consequently as Burgin explains, in his initial example from The Canterbury Tales - Gordon also uses the personal and cinematic memories that he blends, merges and hybridises. His work is a culmination of this.

IV)

My next instance of a significant connection between Burgin’s study and Douglas Gordon’s art comes via the crucial observations of Roland Barthes, and from his text The Third Meaning. Burgin remarks in The Remembered Film that Barthes “had made a closely similar distinction between the ‘obvious’ and ‘obtuse’ meanings of some film stills. We may bring much the same distinction to other images from everyday environments.”[5] This remark then led me to analyse his distinction.

To use Barthes’ own descriptions of both these terms: the ‘obtuse’ meaning and the ‘filmic’ experience, which produce ‘The Third Meaning’, he writes.

First and foremost, obtuse meaning is discontinuous, indifferent to the story and to the obvious meaning (as signification of the story). This dissociation has a de-naturing or at least a distancing effect with regard to the referent (to ‘reality’ as nature, the realist instance).[6]

This meaning has an “infinity” of interpretations and acts on a purely individual human level, much like the ‘punctum’ Barthes defined in photography. It is a meaning which is difficult to define. The viewer connects with a characteristic within a scene which operates entirely separate from the informative or narrative traits within the image. “They extend outside culture, knowledge, information; analytically, it has something derisory about it”.[7] In his examples, this is often evident in gestures, expressions and other such human behaviour.

Also of particular note for me here is the idea of the ‘filmic’. Barthes defines it as this:

The filmic, then, lies precisely here, in that region where articulated language is no longer more than approximative and where another language begins (whose science, therefore, cannot be linguistics, soon discarded like a booster rocket). The third Meaning – theoretically locatable but not describable – can now be seen as the passage from language to significance and the founding act of the filmic itself.[8]

fig vi)

fig vii)

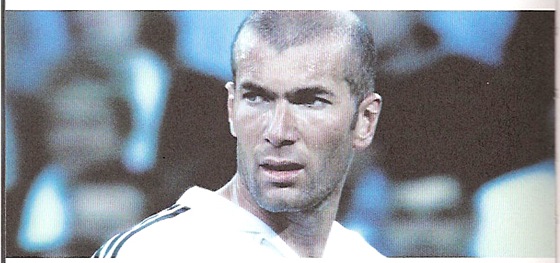

This concept of an indescribable sensation which one gets from an image in a film connects with my final example from Gordon’s cinematic works: Zidane: A Twenty First Century Portrait (2006) (Fig vi & vii), and embodies the notion of the ‘Third Meaning’. In this work what is seen is the famous French footballer Zinedine Zidane (1972- ) being filmed for the entirety of a match. The camera follows him and what is displayed to us is a moving image of remarkable sensibility. Neither narrative nor documentary information is displayed; this film is Gordon’s study of one human being experiencing various levels of mental and physical experiences. Like the expressions and characteristics of the actors that Barthes describes in Sergei Eisenstein’s (1898-1948) movies, it becomes evident that what draws me into this film is Zidane’s subtle idiosyncratic human movements, which Gordon choose to record. To quote Michael Fried (1939- )- who is also fascinated by the ideas of ‘absorption’, and what he calls ‘to-be-seemness’ - from his essay Douglas Gordon and Philippe Parreno’s Zidane:

I see Zidane as belonging to the absorpative current or tradition that has played a central role in the evolution of modern art. But: Zidane’s absorption in the match is not depicted as involving a total unawareness of everything other than the focus of his absorption – in particular, an un-awareness of being beheld that has been the hallmark of absorpative depiction.[9]

I believe then, that moments in this picture provides significant evidence to suggest that what we are viewing is various unconscious thoughts and considerations. This in turn makes for a work which is an embodiment of the ‘filmic’ experience. If one recalls Burgin’s accounts of the remembered scene or image, and Barthes’ ‘obtuse’ meaning, there seems to be a definite linkage with Zidane. What Fried describes are moments which have most resonance, are the untypical images of Zidane.

From time to time he spits. He wipes his face with his arm or sleeve. He scratches his head behind his left ear. Now and then he barks ‘Aie’ or raises one arm asking for the ball. We are also given repeated shots of his legs and feet, including close-ups that reveal him scuffing the toes of his cleats against the turf as he walks along – why does he do that? His gait becomes intimately familiar to us by the end of the film.[10] (Fig viii)

These moments are fascinating as they depict Zidane in an unfamiliar fashion. The uniqueness of this ‘human element’ is profoundly unexpected. Zidane even describes how during specific points in the game he becomes “switched off” to the 80,000 or so crowd watching. This is highly evident in the films images too. The joke he shares with a team mate becomes one of the highlights of the film. A moment Zidane himself had not even recalled and had hated seeing; a “lack of focus” he suggests. What I feel this picture shows are multiple moments of the ‘obtuse’ meaning, and what Burgin describes as ‘Inner Speech’, which is taken from the linguist Lev Vygotsky’s (1896-1934) expression. “In psychoanalytical terms it represents the persistence of the ‘primary process’ that historically precedes ‘secondary’ modes of thought – preferring images to words, and treating words like images.”[11] The images produce a wealth of thoughts and make the overall reading one of infinite possibilities. It has no specific narrative to follow or conscious character development to depict. Above all else, what we see is the individual nature of a human being and the empathy one feels towards them. This, I conclude, produces Barthes’ ‘Third Meaning’.

Epilogue)

What Gordon’s work here begins to visualise are some of the various facets of the ‘mental occurrences’ described by Burgin in The Remembered Film. Whether by the memory of a moment in time, or by images - these works show what it means to be “marked by an image”. They cut across chronology, transcend narrative and shed light on the nature of human perception. Consequently, this understanding of an individual’s inclination to combine ‘filmic’ memories with those from actual ‘real’ events – reveals how ‘fantasy’ has a fundamental function within a person’s psyche.

Bibliography)

Barthes, Roland, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, (Great Britain: Vintage, 1982)

‘Diderot, Brecht, Eisenstein’, in Narrative, Apparatus, Ideology, ed. by Philip Rosen, (New York: Columbia University Press, 1986)

The Pleasure of the Text, trans. by Richard Miller, (Basil Blackwell Ltd: Oxford; United Kingdom, 1990)

‘The Third Meaning’, in Image Music Text, trans. by Stephen Heath, (Flamingo: London, 1984)

Burgin, Victor, The Remembered Film, (Reaktion Books Ltd, London, 2004)

Freud, Sigmund, ‘Hysterical Phantasies and their Relation to Bisexuality’, The Standard Edition of the complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, ed. And trans. by James Strachey, (London,)

Gordon, Douglas, What Have I Done, (Hayward Gallery Publishing: London, 2002)

Douglas Gordon, ed. Russell Ferguson, (MIT Press: United States of America, 2001)

Douglas Gordon: Superhumanatural, (Die Keure: Belgium, 2006)

prettymucheverywordwritten, spoken, heard, overheard, from 1989... Voyage to Italy, ed. Mirta d’Argenzio & Giorgio Verzotti, (Skira Editore S. p. A.: Italy, 2006)

Laplanche, Jean; Leclaire, Serge: Coleman, Patrick, ‘The Unconscious: A Psychoanalytic Study’ (1960), Yale French Studies (Yale University Press: USA, 1972)

Wollheim, Richard, Freud, (Fontana: London, 1971)

[1] http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SjYb6EN0v8w&NR=1, Meet the Artist: Douglas Gordon Part 2 of 2, Q&A with the artist at the Hirshhorn Gallery, 2004, section starts 5minutes 15 seconds.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Douglas Gordon, What Have I Done, chp. 1., ‘Doubles’ (Hayward Gallery Publishing: London, 2002), p.18.

[4] What Have I Done, chp. 3., ‘Beauty’ (Hayward Gallery Publishing: London, 2002), pp. 21-22.

[5] Victor Burgin, ‘The Remembered Film’, The Remembered Film, (Reaktion: London, 2004), p. 66.

[6] Roland Barthes, ‘The Third Meaning’ (1970), Images-Music-Text (Flamingo: London, 1984), p. 79.

[7] Ibid., p.55.

[8] Ibid., p.65.

[9] Michael Fried, ‘Douglas Gordon and Philippe Parreno’s Zidane’, Douglas Gordon: Superhumanatural, (Die Keure: Belgium, 2006), p. 106.

[10] Michael Fried, ‘Douglas Gordon and Philippe Parreno’s Zidane’, Douglas Gordon: Superhumanatural, (Die Keure: Belgium, 2006), p. 107.

[11] Victor Burgin, ‘Introduction: The Noise of the Marketplace’, The Remembered Film (Reaktion Books Ltd: London, 2004), p. 11.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Hello,

We hope you are enjoying Pipe.

We welcome all comments relating to the adjoining article or post and will always endeavor to reply or acknowledge your views. Responses and debates are invaluable to what we do, so we hope you can let us know some of your thoughts.

Please don't however leave comments about anything other than the post(s) read/viewed. Anything irrelevant or what we deem as Spam will be removed.

Thanks for your time.

Kind Regards,

Pipe