II. Melancholy Art: depictive and reflective

When studying melancholy in visual art, we can often recognise cultural and historical traits in the way in which it is described. In the compendium for the catalogue Expressions of Melancholy (from the 2001 exhibition of the same name), at the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Norway; Kari J. Brandtzaeg comments on how the way visual arts was concerned with sensitivity; particularly sensitivity to darkness, yearning and sadness, during the Romantic period (Brandtzaeg, 2001: 7). According to Isaiah Berlin, Romanticism embodied "a longing for the unbounded and the indefinable, for perpetual movement and change, an effort to return to the forgotten sources of life, a passionate effort at self-assertion both individual and collective, a search after means of expressing an unappeasable yearning for unattainable goals." (Berlin, 1990: 92) This longing and sensitivity is evident in the landscapes of the archetypal Romantic Painter, Caspar David Friedrich – for example Abbey in Eichwald. (see figure 6). I chose this particular image by Friedrich for a number of reasons. Abbey in Eichwald depicts many things linked to melancholy, such as the autumnal landscape and a time in

Figure 6. Caspar David Friedrich, Abbey in Eichwald. (1809-10)

the day when daylight meets darkness. We don’t know if it is early morning or early evening which gives it a sense of timelessness. It also contains a ruin, which depicts life’s impermanence. In Nature and Art: Some Dialectical Relationships, Donald Crawford explains how ruins are a visual representation of time passing, and more specifically the qualities of ephemerality, closely associated with melancholy (Crawford, 1983: 55). For me different visual depictions of abandonment are a key way of portraying ‘time passing’, longing and abstract loss linked to melancholy.

In the late 19th century ‘melancholic yearning’ was given a vital new appearance by Edvard Munch. Brandtzaeg describes how Munch inventively managed to ‘charge the human figure with an inner tension interacting with the surrounding landscape’ (Brandtzaeg, 2001: 7). An example of this is Evening. Melancholy I from 1896 (see figure 7). Despite my admiration for his work I find this piece, amongst other similar artworks by Munch, depicting rather than evoking melancholy.

Figure 7. Edvard Munch, Evening. Melancholy I (1896)

Looking at Friedrich’s Abbey in Eichwald and Munch’s Evening. Melancholy I, from a contemporary viewpoint – could it be so that the melancholy these artworks are associated with is bound in history? Or can they still convey melancholy to a present-day viewer? Holly addresses the importance of not forgetting that an individual work of art and the historical constellation of which it is part of “have come from a time and a place that still resonates, and what is past is not necessarily so” (Holly, 2013: xx). In this respect I agree with her. Caspar David Friedrich’s Abbey in Eichwald comes from a world long gone, yet I believe we can still respond to the scene within it. Holly refers to Erwin Panofsky who described that “The humanities . . . are not faced by the task of arresting what would otherwise slip away, but of enlivening what would otherwise remain dead” (ibid: 3). Holly implies that we automatically find life in a work of art because it is within our nature to react to its continuing presence. So, when studying the two previously mentioned images, do they really have the ability to evoke melancholy in the viewer? Is there still something there for us to relate to? Or is it possibly just an impression of melancholy that they depict? As I mentioned, Munch’s Evening. Melancholy I, left me wondering if it depicts rather than evokes melancholy. I believe it is bound in the history of melancholy due to ‘the melancholic pose’, which informs us of what the image is about almost as much as the title does. The pose; ‘head in hand ‘has been represented again and again throughout the history of Art. Albert Dürer’s Melancholia I from 1514 (see figure 8) is one of the most famous examples of this. The solitary figure lost in thoughts, with its head in its hands has throughout the centuries come to represent a typical portrayal of “the melancholy mood” (Brandtzaeg, 2001: 5). According to Raymond Klibansky’s research on Dürer’s engraving in Saturn and Melancholy, the primary

Figure 8.. Albert Dürer, Melancholia I (1514)

significance of this age-old gesture is grief, but it may also mean fatigue or creative thought (Klibansky, 1964: 285-6). This might be why I find Munch’s Evening. Melancholy I, just depicting ‘the historical representation’ of melancholy. Whereas I deem a landscape painting, like Friedrich’s Abbey in Eichwald being far less bound in history. For me it represents a past and a history that still exists. As a result this image manages to evoke something within me; it enlivens what would otherwise remain dead.

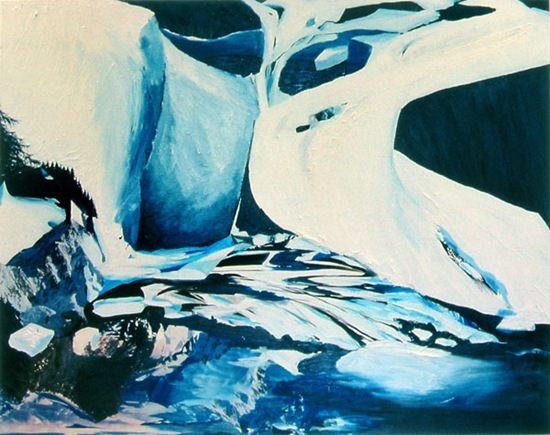

Of course, landscape paintings like Abbey in Eichwald are also entwined in art history relating to melancholy. Could this restrain some our perception of such a painting? In Melancholy, Mood and Landscape, Jennifer Radden discusses whether melancholy possibly has some ‘reinforced associations’? - If it contains connotations intertwined with the iconographic traditions of Western European visual art? She discusses whether “the melancholy landscape makes us think of, rather than feel, melancholy, and particularly to think of mood states of unexplained disquiet and sadness?” (Radden, 2007: 46). Radden wonders why we describe bleak, wintery landscapes with featureless spaces as ‘melancholic’. She links these connotations to the history of melancholy and in particular its relation to mental illness. I deem she has a point. In History of Madness Michael Foucault describes the mental world of melancholy as “damp, heavy and cold” (Foucault, 2006: 272). This description pictorially defines much of the visual artwork that we often refer to as melancholic. Friedrich’s Abbey in Eichwald and recent images such as Peter Doig’s Echo Lake or Sigrid Sandström’s Original Hrönir (see figures 9 and 10), might all simply carry the impression of melancholy?

Figure 9. Peter Doig, Echo Lake (1998)

Figure 10. Sigrid Sandström, Original Hrönir (2003)

I think these kinds of melancholy artworks are too complex to just ‘carry the impression of melancholy’. Thus, I surmise that we still intuitively attach expressive characteristics such as melancholy, to some pieces of visual art because they initially produced feelings linked to transience and abstract loss within us. We merely ‘just use’ the word melancholy as a description of what they make us feel – since recollections linked to melancholy are the closest to what we believe we have experienced when we first saw them. Where Radden asks how “aspects of the landscape make us think of, not […] feel, melancholy” (Radden, 2006: 47), I believe that if we start thinking of something as being ‘melancholy’, the feeling itself is already lost. Melancholy only ‘exists’ within us when we experience it. If someone describes a landscape painting as melancholic, it only gives us an idea of what we could expect based on the cultural and historical ‘reinforcements’ that Radden talks about. It doesn’t necessarily mean that we will experience it as ‘melancholic’.

So, where I find the ‘head in hand’ pose too symbolic and historically bound, I conceive that a landscape can have natural qualities that may have the ability to transfer

Figure 11. Karin Andersson, Leftover’s (2006)

melancholy to its viewer. However, this does not only apply to landscapes, certain ‘figures’ and ‘settings’ can also trigger melancholy. For me Mamma Karin Andresson’s Leftover’s (see figure 11), is an example of that. In this image there are no autumnal landscapes or lonesome figures. Perhaps it is its mundane nature – the unmade beds or a vague familiarity that evokes a somewhat melancholic feeling in me? Whatever it is, I find there are a lack of history bound connotations to adequately define this image.

To surmise, I think melancholy artworks can exist as either producers of the sensation of melancholy; or producers of the representation of melancholy - and in some cases - as both. I agree with Holly, who suggests that melancholy in visual art can find its own way, since it reflects a past that never really existed (Holly, 2013: xiii). It can still evoke a feeling originally aroused in this past, within the viewer. I deem the kind of artworks that provide us with this sensation of melancholy being reflective in a similar way to how Boym describes reflective nostalgia (Boym, 2001: XVIII).). This kind of melancholy is what really intrigues me. A piece like Peter Doig’s Man dressed as Bat(see figure 12) is an subtle figurative example of this. I find this piece possessing a rare sensitivity; the transparent creature warily seeking the attention of the viewer. A more obvious example which in my view manages to both depict and convey melancholy is Anslem Kiefer’s leaden plane Melancholia (see figure 13). Both the title and the use of the polyhedron in Kiefer’s Melancholia creates a bond with Albert Dürer’s Melancholia I (see figure 8) obvious to anyone acquainted with Western art history. Kiefer’s airplane might not be a landscape but it connects with Radden’s discussion about how melancholy art contains ‘connotations intertwined with the iconographic traditions of Western visual art’. However, I don’t find this piece bound in history in the same way as Munch’s Evening. Melancholy I. I think that Kiefer manages to use the history of melancholy in an innovative way – he subtly borrows Dürer’s polyhedron, which according to Klibansky is ‘both a problem […] and a symbol of […] perspective (Klibansky, 1964: 328). Kiefer’s piece reminds us of many problems faced by humanity. The exhausted airplane recalls the consequences of World War II. However, just as it recalls the aftermath of the War, it also reflects and represents the beginnings of a ‘new’ post-war era in modern history, and the loss and divisiveness that came with it. For me Kiefer’s Melancholia suggests how closely related human progress and destruction are. Its significance to my discussion lies in its links to the past and in its ability to ‘evoke a sensation of loss’ in the viewer. Behind this piece’s direct and seemingly clear melancholic historical associations, lies an ability to start a thinking process which in itself can evoke melancholy in the viewer.

Figure 12. Peter Doig, Man Dressd as Bat (2007)

Figure 13. Anslem Kiefer, Melancholia (1990-91)

For me the loss and the passing of time linked to melancholy became just as evident when I encountered Kiefer’s Melancholia as it did when I saw Peter Doig’s Man dressed as a Bat, even if it manifested itself in very different ways. Whilst Kiefer’s Melancholia left me thinking about devastation and life’s transience, Doig’s Man Dressed as a Bat managed to affect reminiscent longings for home within me. In both cases, melancholy was the basis for these associations and thoughts. In dissimilar ways both these artworks make it evident that the aftermath of melancholy can affect our perception of images by transporting us into deeper consciousness.

In this examination of melancholy art I have started to identify how different visual artworks can evoke new implications and create different feelings of loss. Representations of melancholy vary, and as each decade passes and artist’s forms of expression change, they become greater and more complex.

Even if the works of art I have highlighted in this essay all have very dissimilar motifs and descend from very different eras, ‘the melancholic moods’ that many of them – at least when I first saw them – managed to induce within me are ‘real’. Perhaps it is the feeling of loss, together with its connection to the sensation of abandonment that gives these images the capacity to ‘strike’ ‘that melancholic cord’? This is what I find so hard to pinpoint. Whatever it is they manage to stir up within me, I deem that when we view certain visual artworks, they sometimes manage to help us find those ‘fragments of our own existence’ which Benjamin suggests can help us understand our past. (Zizzelberg, 2007: 296-97). Even if these images do not always permit us to enter ‘the melancholic sphere’, they do at least have the ability to ‘preserve melancholy longing’, as Zisselberger describes it (ibid: 297). Holly uses a quote by Chirstoffer Bollas that fittingly describes why melancholy in visual art is so captivating: A work of art can give the viewer “the sense of being reminded of something never cognitively apprehended but existentially known […] this experience originates as a crystallization of time into a space where objects and subjects achieve and intimate wordless rendezvous” ( Holly, 2013: 19). That in itself is a unique quality which we should not underestimate. It highlights how melancholy is and has always been an important part of the human temperament.

Epilogue

Melancholy has a long and complex history. Sometimes its past, with all its connotations becomes more of a burden than an explanatory part of its fleeting existence. Still our interpretation of the term today is heavily influenced by this multifaceted past. The way in which many contemporary writers and artists describe ‘the essence of melancholy’ is somewhat less depressing than the majority of the terms historical connotations. However the term still carries traits from both Freud’s interpretation of melancholia and from the “emotional vulnerability” he claimed to have found in our experience of transitory and ephemeral phenomena.

Melancholy’s complexity becomes evident to us when we examine historical and contemporary artworks that seemingly possess melancholic traits. We can differ between the kind of artworks that ‘just’ depict melancholy and the kinds that also manage to evoke melancholy. For me the latter ‘kinds’ are the true carriers of ‘the essence of melancholy’. This is what I find so intriguing. Holly points out that “one certainly does not need to be a skilled art historian to become enraptured by a particular work of art, and then to become melancholic upon leaving it” (Holly, 2013: xii). For me this is the key to ‘Melancholy Art’. It has the capability to touch anyone. In my view the melancholic feelings that visual artworks can evoke within the viewer are not to be overlooked. These feelings arise because they carry fragments of our past. In many ways they manage to ‘release’ artworks from the time in which they were made. This gives melancholy a peculiar relatedness to time and to our past. Through my research I have also learnt that even after the sensation of melancholy leaves us it can affect our perception of images by transporting us to another level of consciousness. For me this kind of melancholy found in certain art works, is reflective and not “bound in history” but informed by it.

I may never be able to totally comprehend melancholy’s real meaning, but I have learnt that it contains many layers of interpretation. By my considered judgement, melancholy will continue to exist and develop with every generation of civilisation. It is part of the human temperament; possessing a unique ability to make us aware of a past that has become abandoned by our memory – our Forgotten Self. For that reason the presence of the familiarity it carries will always be welcomed by us.

Figure 14: the Circulation Proceeded Unnoticed (2013)

Bibliography

Benjamin, Walter. (2002). Berlin Childhood around 1900. In: Selected Writings, vol. 3: 1935-1938. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Benjamin, Walter. (1985). The Origin of German Tragic Drama. Suhrkamp Verlag.

Berlin, Isaiah (ed. Henry Hardy). (1990). The Crooked Timber of Humanity: Chapters in the History of Ideas. John Murray

Bollas, Christopher. (1987). The Shadow of the Object: Psychoanalysis of the Unthought Known . Columbia University Press.

Boye, Karin. (1994). Complete Poems. Translated by, Duff, David. Bloodaxe Books.

Boym, Svetlana. (2001). Future of Nostalgia, Basic Books.

Boym, Svetlana. (2007). Nostalgia and it disconcerts, At: http://www.iasc-culture.org/eNews/2007_10/9.2CBoym.pdf (Accessed on: 05.04.13)

Brandtzaeg. J. Karl. (2001). Expressions of Melancholy. Exhibition Catalouge. The National Museum of Contemporary Art, Olso, Norway.

Crawford, Donald. (1983). Nature and Art: Some Dialectical Relationships. In: Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, No: 42, 1983. p.26-29.

Dillon, Brian. Anatomy of a Cloud. In: Sandström, Sigrid and Atopia Projects (eds.). (2006). Grey Hope: The Persistence of Melancholy. Atopia Projects, p 26-29.

Foucault Michel. (2006). History of Madness. Routledge

Freud, Sigmund. (1915). On Transience. At: http://www.psptraining.com/readings/Freud,%20S.%20(1953-74).%20On%20transience%20(1919).%20The%20standard%20edition%20of%20the%20complete%20works%20of%20Sigmund%20Freud%20(v.14,%20pp.304-307).pdf (Accessed on 09.03.13)

Freud, Sigmund. (1917). Mourning and Melancholia. At: http://www.free-ebooks.net/ebook/Mourning-and-Melancholia/pdf/ (Accessed on 05.03.13)

Gustafsson, Lars. Time Pain and Loss. In: Sandström, Sigrid and Atopia Projects (eds.). (2006). Grey Hope: The Persistence of Melancholy. Atopia Projects, p 56-61.

Holly, Ann, Michael. (2013). The Melancholy Art. Princeton University Press.

Kafka, Franz. (1979). Conversations with the Supplicant. In: Description of a Struggle and Other Stories. Penguin

Krauss, Rosalind. .(1986) Photography in the service of Surrealism In . Amour Fou: Photography and Surrealism. Krauss, Rosalind and Livingston, Jane. London: Arts Council of Great Britain.

Radden, Jennifer. Melancholy, Mood and Landscape. In: Sandström, Sigrid and Atopia Projects (eds.) (2006). Grey Hope: The Persistence of Melancholy. Atopia Projects, p.46-56.

Sandström, Sigrid (with Gavin Morrison). Grey Hope. In: Sandström, Sigrid and Atopia Projects. (eds.) (2006). Grey Hope: The Persistence of Melancholy. Atopia Projects, p.6-9.

Sarafianos, Aris. (2004). The many colours of black bile: the melancholies of knowing and feeling. At: http://www.surrealismcentre.ac.uk/papersofsurrealism/journal4/acrobat%20files/Sarafianos.pdf (Accessed on: 05.02.13)

Schopenhauer, Arthur. (1964). On the Vanity and Suffering Of Life. From: The world As Will And Representation. Translated by: E.F.J Payne. Vol. 1, Fourth Book . Dover Publications.

Tarkovsky, Andrei. (1989). Sculpting Time- Reflections on the Cinema. Translated by Hunter-Blair, Kitty. Faber and Faber.

Zisselberger, Marcus. Melancholy Longings: Sebald, Benjamin, and the Image of Kafka. In: Lise Patt with Christel Dillboher (eds.). (2007). Searching for Sebald, Photography after W.G. Sebald . The Institute of Cultural Inquiry and ICI Press.

Films:

Directed by Andrey Tarkovsky (1988). Directed by Michal Leszczylowski [DVD]. Sweden. The Swedish Film institute. SFI.

List of Illustrations:

Figure 6: Caspar David Friedrich. (1809-10). Abbey in Eichwald [Oil on Canvas, 110.4 x 171 cm. Courtesy of Schloß Charlottenburg, Berlin] At: http://www.bc.edu/bc_org/avp/cas/his/CoreArt/art/resourcesd/fri_abbey.jpg (Accessed on 03.04.2013)

Figure 7: Munch, Edward. (1896). Evening. Melancholy I. [Woodcut, 41.2 x 45.7 cm. Courtesy of MoMA, New York.] At: http://www.moma.org/collection_images/resized/669/w500h420/CRI_61669.jpg (Accessed on 03.04. 13)

Figure 8: Albert Dürer. (1514). Melancholia I. [Engraving, 24 x 19 cm. Courtesy of the British Museum, London] At: http://www.artfund.org/what-we-do/art-weve-helped-buy/artwork/158/melancholia (Accessed on 09.04.13)

Figure 9: Peter Doig. (1998). Echo Lake. [ Oil paint on Canvas. 230 x 360 cm. Courtesy of Tate, London] At: http://www.tate.org.uk/art/images/work/T/T07/T07467_10.jpg (Accessed on 15.04.13)

Figure 10: Sigrid Sandström. (2003). Original Hrönir [acrylic, collage, oil on board, 48x60”/122x153cm] At: http://www.sigridsandstrom.com/painting_files/2003_files/original_hronir122x153cm.jpg (Accessed on 30.03.13)

Figure 11: Karin Mamma Andersson (2006). Leftovers. [Mixed technique. Private Collection] At: http://blog.mutewatch.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/Mamma_Andersson_Karin-Leftovers.jpg (Accessed on 22.03.13)

Figure 12: Peter Doig. (2007). Man Dressed as Bat. [Oil and distemper on linen, Courtesy of Michael Werner Gallery, London] At: http://www.artnet.com/Images/magazine/reviews/robinson/robinson2-6-09-6.jpg (Accessed on: 03.03.13)

Figure 13: Anselm Kiefer. (1990-91). Melancholia. [Led airplane with crystal, 320 cm x 442 cm x 167 cm, Courtesy of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art ]. At: https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEj8xJ3YbJJh_yRBC0oq9aOFQ2s9mkeRneQ04o_ngwM3hWdYcXCo1kboQo65yX7lsygUfvbn5ScDtmpKA1Gnpl73wQeBnegaSURaJ3ixKXWLTX_tzs54zWtrWtP2cvMf5RQe7cNh06FoYZI/s1600/sfmoma_Fisher_15_Kiefer_Melancholia.jpg (Accessed on: 03.03.13)

Figure 14: Glantz, Anna. (2013). the Circulation Proceeded Unnoticed. [Illustration, acrylic, gouache, and ink on paper] In possession of the author: Canterbury.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Hello,

We hope you are enjoying Pipe.

We welcome all comments relating to the adjoining article or post and will always endeavor to reply or acknowledge your views. Responses and debates are invaluable to what we do, so we hope you can let us know some of your thoughts.

Please don't however leave comments about anything other than the post(s) read/viewed. Anything irrelevant or what we deem as Spam will be removed.

Thanks for your time.

Kind Regards,

Pipe